For quite some time now, I’ve been thinking a lot about the nature of music. Asking “The Big Questions”. For instance, why? Why do people create music? Why do people listen to music? Why do people connect so strongly with music?

The answers to those questions vary from individual to individual. People perform music for different reasons, and people listen to music for different reasons, all of which are completely valid insofar as the individual goes.

Recently, I was listening to one of Bach’s pieces (I think it was one of the Brandenburg Concertos) and a new question struck me. I started to consider all of the things that came together for the simple act of me listening to this piece of music. And, the more I learned about music theory, music history, and technological developments in music, the more complex the layers to this question became.

The question that struck me was this; why do humans expend so much energy on creating music?

Author’s note: What follows is primarily focused on Western Music. Notes, scales, music notation methods, and instruments vary from culture to culture. But, the point I’m making remains no matter which cultural phenom you drop in

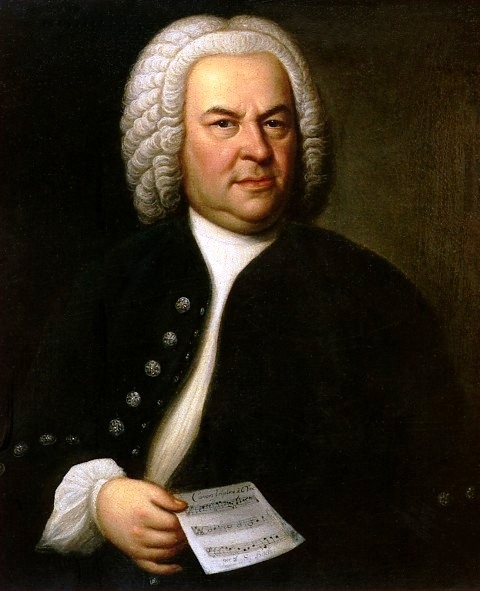

I said this question came to me while listening to Bach. So, how did Bach lead me on this philosophical journey into the nature of music?

This is Bach.

Johann Sebastian Bach was a German composer and musician who lived from 1685 – 1750. He was a phenom even by today’s standards. He finished over 1000 pieces of varying forms for a variety of instruments. He took many period elements (such as four-part harmony, modulation, and counterpoint) and pushed them to levels of development never before achieved. From the guitar shredder to the pop vocal group – every musician performing today draws something from the lineage of Johann Sebastian Bach.

As impressive as all that is, Bach (and other composers and performers) are merely the agent of expression. Many other things had to happen to give Bach the tools he needed to express his thoughts. Bach may be one of the greatest musical minds that has ever lived, but a lot of musical stuff proceeded him.

Please Make A Note Of It

The most basic thing in music is a note. Notes are ways to give frequencies of sound a name. For example, C4 (also known as “middle C”) is the name we give to the frequency 261.63 Hz (we talked a little about frequencies and Hz last time).

Notes are grouped together in scales. A scale is a way to determine the range of notes that can be played in a given piece. But, Bach didn’t come up with the note C nor any of the scales it belongs to. Someone else had to do that first.

Believe it or not, there is a lot of math involved with musical notes, scales, and theory. I won’t get into it here. But, the same guy who determined that if you took one side of a triangle, squared it, and added that to the square of the second side of the triangle, you would get the square of the hypotenuse (a2 + b2 = c2) is the same guy who determined there was a mathematical relationship between notes that fit together in a scale. That was Pythagoras. He lived from 570 BC – 495 BC. Over 2000 years before Bach was born.

Write It Down!

Musical ideas usually come to musicians in chunks. A theme may not be fully developed when the musician starts to play something new. When an idea comes to a modern musician, they likely pull out their phone, hit record in a recording app, and hum a few bars of the new idea so they can refer back to it later. In the 7th century, archbishop Isedore of Seville wrote “unless sounds are held by the memory of man, they perish, because they cannot be written down.”1

Bach didn’t have the luxury of being able to whip out his iPhone and hum a few bars of his next concerto into it so he wouldn’t forget it. He had to use a different method.

Also, Back wrote music for more than one instrument. imagine how hard it would be to communicate what you wanted someone else in the orchestra to play if you had to give them verbal directions the whole time. It would be a nightmare. The better way would be for you to give them written instructions so they could follow along while playing. Imagine Bach sitting at the keys of his harpsichord and trying to shout to the violinist and cellist what they should be playing and how at a given moment.

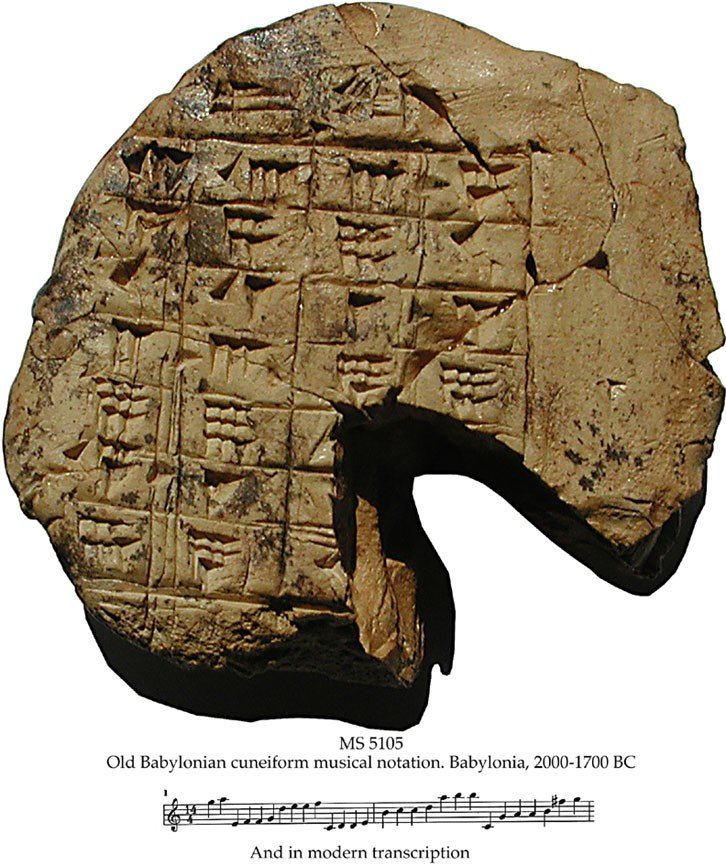

Musicians realized these problems very early on. They realized they needed a way to write down their ideas so that 1) they wouldn’t be forgotten and 2) they could be performed the same way over and over again. The earliest evidence we have for music in written form comes from a cuneiform tablet that was discovered in Babylonia (modern-day Iraq). The tablet dates back to 1700 BCE. So, this has been a problem for musicians for a really long time.

The standard form of musical notation we use today is known as staff notation (an example of it appears in the image above). It was developed by the Benedictine monk Guido d’Arezzo who lived from 991 to 1033. Guido wanted a way to standardize the teaching and performance of the liturgy, so he came up with a written method to do that2.

Staff notation is only one of many forms of written musical notation. Cultures across the globe have developed written languages that serve one purpose – to help people play music. They combine symbols and drawings and images (and words) that can’t be used for anything else but to play music. You can’t use them to create legal documents or tell a story (directly, at least) or give instructions for baking a cake. The only purpose for the various languages of musical notation is for the performance of music.

Tickle The Ivories

We could stop with notes, notation, and a singing voice and be done with human musicality. But, humans did something else – we created instruments. Someone had to invent the harpsichord, the violin, and the cello before Bach could use them in his arrangements.

Many instruments can trace their origins to starting as something else entirely. For example, what we know as the modern trumpet can be traced back to the usage of hollowed-out animal horns as signaling devices. Signaling others of danger or signaling soldiers on the battlefield would be very practical reasons for such instruments.

A horn is used because it can be heard from further away than shouting (depending on the length of the horn) and is more distinguishable. Also, one person trying to shout over a bunch of other people already shouting just sounds like more shouting. So, using animal horns has a utilitarian purpose and gives the blower of the horn a mechanical advantage to complete a task (signaling troupes).

We see this in many animal species as well. For example, the title of Loudest Land Animal goes to the Howler Monkeys that live between southern Mexico and Argentina. Their vocalizations can get as loud as 140 dB. By comparison, a human shout is around 88 db. So, humans need amplifiers to get over loud noises across distances.

However, the instruments used in the Brandenburg Concertos are violins, violas, cellos, and a harpsichord. None of these do a darn bit of good if you are trying to signal “HALT!” to a marching armed force. No, these noisemakers serve a different purpose.

Stringed instruments – like banjos, guitars, and violins – are used almost exclusively to create aesthetically pleasing sounds. Sure, they can emit sounds that aren’t pleasing. But, when they do that, we say they are out of tune. Or “bad” versions of the instrument.

Many instruments are crafted to have visual and aural beauty. This is because they are made by craftsmen. A craftsman ( or woman) cares very deeply about the things they make with their hands. A craftsman wants the item he or she has created to fulfill its purpose as perfectly as possible (in this case, make sounds that have a certain tonal quality). They also want the things they make to look good.

Take, for example, this harpsichord.

I’ve looked up images of many harpsichords. They have a body that contains all of the inner workings of the instrument. This body sits on legs that raise it off the ground. All that is required to achieve this goal would be simple, straight legs. But, every single harpsichord you will find pictures of has some sort of design to the legs that displays a certain level of skill required to make them. Some are curved, some have designs carved into them, some have ornate feet, some have knobby knees. But, none of them have simple stick legs. Even the legs in the image above are not simple.

Why? The added flourishes don’t add anything to the sound of the instrument. They don’t amplify it or make it sound better. They are just there to make the instrument look nice. They (and the choice of wood, the finish, and the contrasting inlays in the example above) are only there because the person who built this harpsichord cared very deeply about the visual beauty of the thing as much as they did the tonal qualities of the thing. Even though the visual aesthetics have nothing to do with the thing fulfilling its purpose.

The visual beauty of this particular “noisemaker” is valued so much that it is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

If You Build It They Will Come

Crafting things that affect music doesn’t stop with the instruments. Entire buildings are designed and constructed for the sole purpose of enhancing music. All the building materials that get used, all of the angles you see, the way the seating is arranged – the entire room is designed to make the music sound a certain way.

One of the most famous places tied to Bach is St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, Germany, where he was the Thomaskantor (“director of music”) from 1723 until his death in 1750.

Most Protestant churches of the Baroque period were constructed in what is known as the Gothic style. They are characterized by steep-pitched roofs, angular spires, and large stain-glassed windows. Inside, their walls are often covered with plaster and wood paneling. Each of these elements – the materials used and the shape of the structure – plays a role in the acoustics of the space. They are designed to make certain types of music sound great (in this case, organs and orchestras).3

The same can be said for Orthodox churches, but for a different style of music. Orthodox churches typically feature a dome atop a tall drum-like structure. Inside, there are lots of arches. The walls are primarily masonry covered in plaster. These design elements are selected to complement the style of music of the Orthodox church—chanting and singing.3 The domed structure allows the voices of the choir to reverberate around the nave in such a way that the sound seems to be coming from Heaven itself.

The music of Bach sounds terrible in these places.

So What?

I started this article off by saying something dawned on me when I listed to the Bach. So, what exactly was that? Well, as I listened, and I thought about all of the points I have raised above, I concluded that the way humans relate to music is way, way, way different than the way animals relate to music. Animals use of music doesn’t go much further than a means of communication. Humans have created written languages, crafted devices to make music that are both pleasing to hear and see, constructed beautiful structures out of specific materials intended to enhance the sound, and some will spend hours and hours almost every day trying to perfect their ability to make sound.

Humans are not like animals. Some may even say they are specially created.

- Isidore of Seville (2006). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville (PDF). Translated with introduction and notes by Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach, and Oliver Berghof, with the collaboration of Muriel Hall. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83749-1. ↩︎

- Otten, J. (1910). “Guido of Arezzo”. The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company ↩︎

- Gould, A. (2021) Acoustical considerations in Orthodox Church Design, Orthodox Arts Journal. Available at: https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/acoustical-considerations-in-orthodox-church-design/ .

↩︎ - Gould, A. (2021) Acoustical considerations in Orthodox Church Design, Orthodox Arts Journal. Available at: https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/acoustical-considerations-in-orthodox-church-design/ .

↩︎

David is an author and speaker with Legati Christi where he has written about and spoken on multiple apologetic and theological topics for the past 6 years. He recently launched Theology In Music as a way to combine his love of theology with his other passion in life – music.

Leave a Reply